I know I say the same thing after reading every book, but this is seriously an important book for normal people (i.e. non-China experts) attempting to wrap their head around modern-day China. I must admit, the read turned into somewhat of a grind toward the middle when author Johnathan Spence goes out of his way to extensively quote long poems and writings from various Chinese intellectuals from all walks of life, but as you approach the final quarter of the book, it all comes together beautifully.

Ultimately, the poems and lengthy excerpts from short stories actually serves their purpose. They help readers understand the psyche of the average Chinese. The reader begin to learn why China is so vastly different than western nations, which greatly adds to the empathy quotient when assessing the country. Spence does a great job in giving on-the-ground perspectives of critical events over the past 150 years that helped to mold the brains of modern-day Chinese.

This book is also important because it was written at a time when most of the world was somewhat closed. I’m talking pre-gobalization. Pre-Tiananmen Square Massacre. Pre-Fall of the Berlin Wall. Pre-unipolar United States-gets-to-make-a-lot-of-important-geopolitical-decisions. Those are all very important pre-world-shaping events that tend to make one biased or nudge western historians to think inside well-defined singular tracks that tend to weigh heavily on liberalism, capitalism, democracy, etc.. Johnathan Spence actually had a nice, long walk around China. He allowed himself time to read large bodies of works by Chinese poets, writers, and review other works of arts. It was the great media critic Marshall McLuhan who wrote in his must-read “Understanding Media”, “The artist picks up the message of cultural and technological challenge decades before its transforming impact occurs.” This statement is proven through the works of all the artists that Spence features in the book.

Along with more prominent names we’ve come to know in the west like Sun Yatsen, Mao Zedong, Chiang Kai-shek, Deng Xiaoping, the reader is introduced to a long list of not-so-famous names (in the west, that is) of writers and revolutionaries who shaped modern Chinese thought like Kang Youwei, Qiu Jin, Liang Qichao, Zhou Enlai, Zoo Rong, Ding Ling, Xu Zhimo, Lu Xun, Lao She, Bei Dao and many, many more. Let’s just say that Spence has a bibliography that spans 21 pages, so for those you who like hopping from book to book using an author’s primary sources, I wish you good luck.

Before I close, I want to spend a little time discussing my main takeaways from the read. It took a couple months of constant chewing, cross referencing Wikipedia and other sources to add additional context, but it was time well-spent in that it opened the flood gates of empathy for Chinese people and culture. Just like people in any nation around the world, the main driver is not a particular government ideology, but rather nationalism. But, unlike people in any nation around the world, the Chinese people have roughly 3,500 years of written history and probably another couple thousand years or more of oral history to help fan the flames of nationalism!

Spence invests considerable amount of time on writer and political reformist Kang Youwei to help build a strong foundation for his 100-year long narrative. I’ll admit, I was shocked at some of the stuff I read and I’m assuming that’s mainly because I hadn’t read much of Chinese political or cultural thought before. Let’s just say that Kang Youwei was way ahead of his time. Firstly, he was quick to realize that the Chinese people weren’t ready to jump from authoritarian rule to western-style democracy in one full swoop as certain factions inside and outside China hoped. He favored gradualism because he felt the west would simply exercise control over all of China by way of dividing one part against another. Sound familiar, countries in the Middle East or former Soviet states?

Spence writes, “In two careful and lengthy letters written to Liang and to overseas Chinese, Kang reasserted the need for gradualism if China was to avoid being partitioned by major Western powers and Japan. A restored emperor, even though Manchu, working constructively with Chinese and Manchu officials, could establish a strong and legitimate government. To leap from Autocracy to a republic would not be possible without chaos, wrote Kang, developing arguments that he had been thinking through for at least a year concerning both the inevitability of eventual democratic forms and the need to pass through each measured historical stage.” (p. 32)

In another passage, Spence adds some clarification on Kang’s thinking: “He [Kang Youwei] reinterpreted Confucius to suggest that the developments he presented lay in the future: China had come thru the Age of Disorder, on this interpretation, but could not simply leap into the Age of Universal Peace without first joining the Western powers and Japan in the slow move through the Age of Ascending Peace. There were thus no shortcuts to the Great Community, although in reflecting only had Great Community one could begin to plan the future of a better and happier world.” (p. 33)

Some of the stuff coming out Kang Youwei was very deep:

I was born on this earth, so I come from the same womb as humans in all countries, even though our body types may be different. I know of them and so I love them. I have drunk deeply of the intellectual heritage of ancient India, Greece, Persia, and Rome, and of modern England, France, Germany, and America. I have pillowed my head upon them, and my soul in dreams has fathomed them. With the wise old men, noted scholars, famous figures, and beautiful women of all countries I have likewise often joined hands, we have sat on mats side by side, sleeves touching, sharing our meal, and I have grown to love them. Each day I have been offered and have made use of the dwellings, clothing, food, boats, vehicles, utensils, government, education, arts, and music of a myriad countries, and these have stimulated my mind and enriched my spirit. Do they progress? Then we all progress with them. Do they slide backward? Then we all slide with them. Are they happy? Then we are happy with them. Do they suffer? Then we suffer with them. It is as if we were all parts of an electrical force which interconnects all things, or partook of the pure essence that encompasses all things.

Here’s Spence adding context to what Kang imagined as the Great Community.

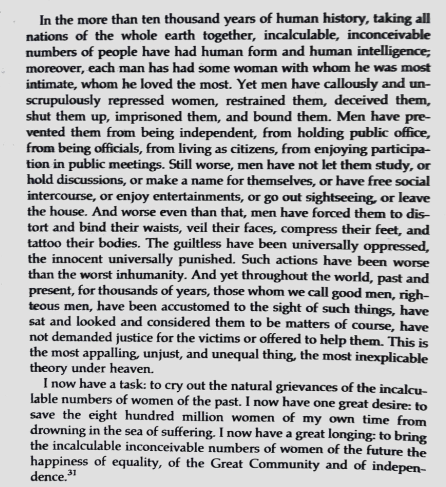

Also I think it is worth mentioning that what Kang wanted was equality for all, freedoms of all types and generally a very democratic society, but he thought this was an eventual destination that China would one day reach, but it would take time. Here’s a taste of Kang’s writing about women in his seminal work “Book of the Great Community” (or “Great Unity” as it is known in other circles):

Obviously, I could go on and on with the rest of the literary lineup listed before, but I wanted to give a sampling of one of the prominent thinkers in China during the country’s transition from pure authoritarian rule to eventually communism. For those of you made it this far, I’m telling you, opening this book is going to open up a whole new way of thinking about China. This type of thinking will be very important as soon as the United States comes back to its senses and moves on from its very Euro-centric foreign policy and turns its attention to where it should be: China. Grab a used copy today!

Leave a comment