I must start off by admitting that I initially misjudged this book, but after a few pages into it, I quickly came to realize it was a special piece of work that weighed heavily on its subtitle: “Study of the Place of Pictorial Art in Muslim Culture.”

What I assumed would largely be a work glorifying intricately painted floral tiles and beautiful Islamic calligraphy inside famous mosques around the world took a sharp turn for what even-not-so-orthodox Muslims might perceive as bordering on blasphemy.

I’ll be honest, there was definitely a level of guilt I had to ascend before allowing the information to properly soak in. Those feelings, I’m assuming, hinged on the fact that I was viewing something that was always culturally shunned upon. The information was also creaking open doors to hidden away areas of research that had long been shut. It was almost like uncovering a big secret that was wrapped into oblivion with some sort of religious caution tape that alerted the nosy and dangerously curious to move along. Either I’ve made you a little curious or completely turned you off, but I felt I had to be honest in giving some context behind my personal reading.

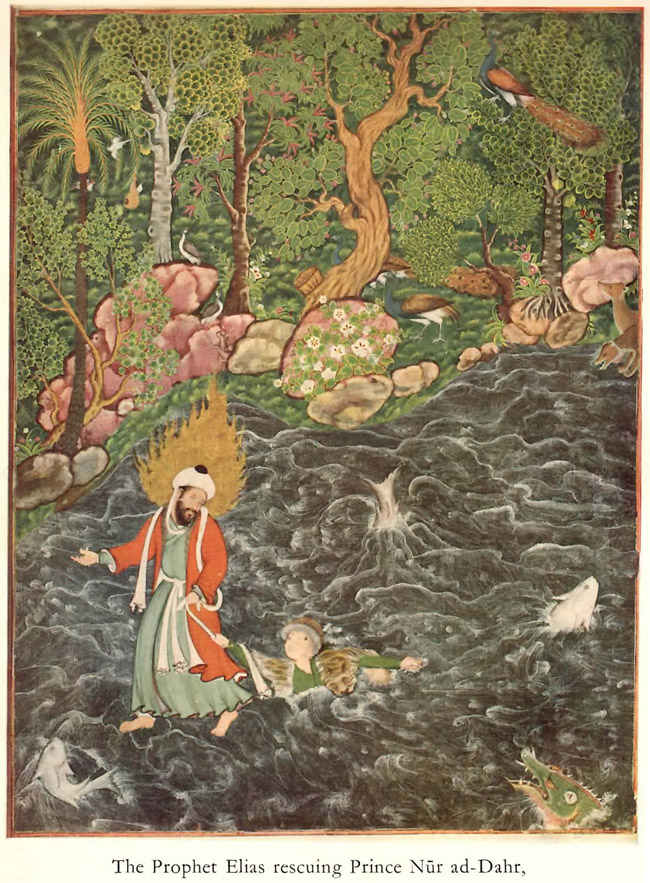

The opening image is a special one. I was literally floored at the level of detail (the scan isn’t so good, unfortunately). The leaves, stones, wildlife, water flowing, etc.—all pull in the viewer. Simply a visual treat, to say the least.

With all that in hand, let’s move our attention to the actual contents of the book.

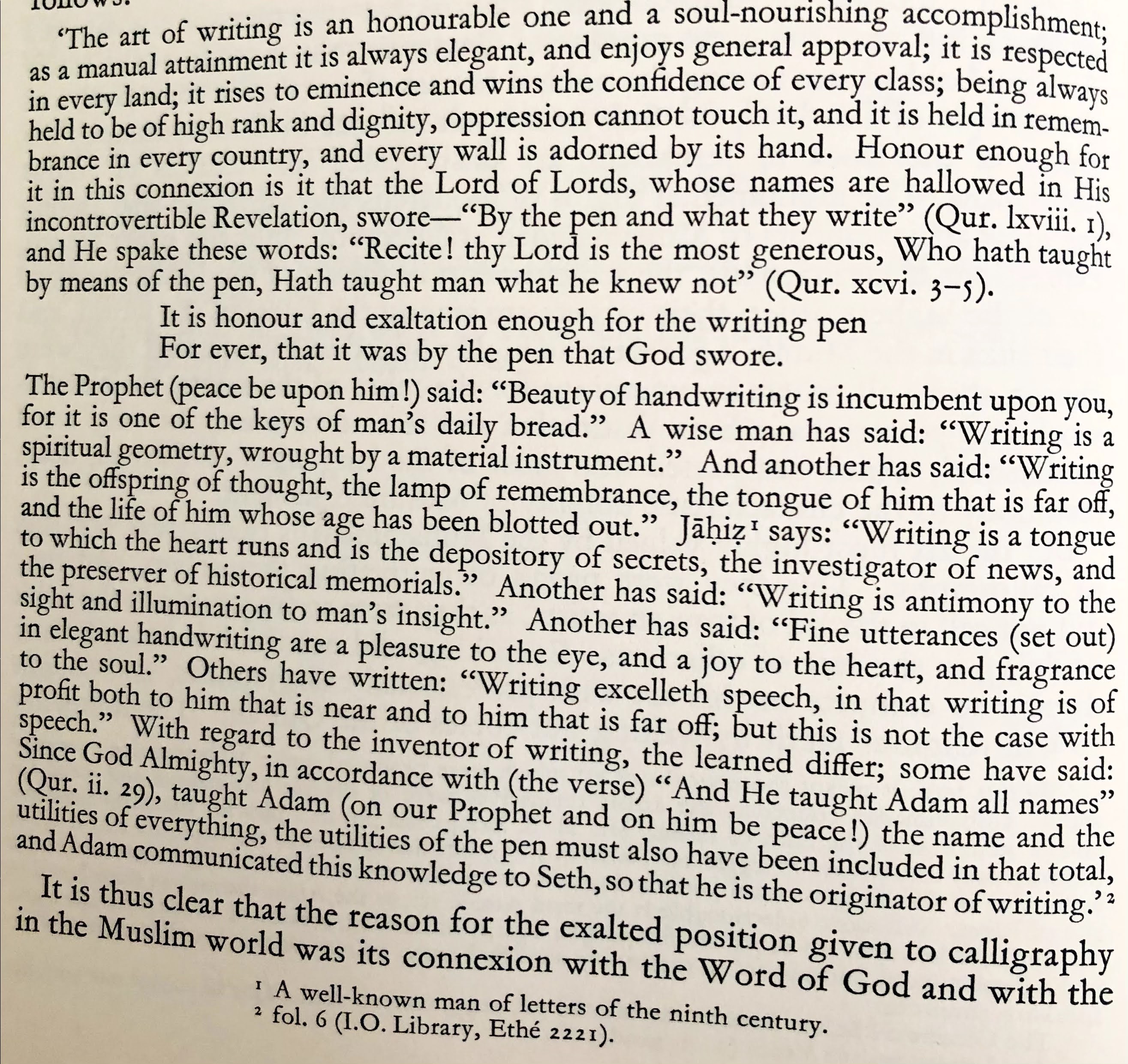

Author Sir Thomas Arnold begins his book by first contrasting the level of respect that is showered upon calligraphy as an art form as opposed to painting. Apparently, even the mere mention of painting or biographical information about painters is difficult to find among all the historical archives scattered inside various museums and libraries across the globe. As an example, Arnold cites a very beautiful excerpt from a 14th century historical work titled Nafa’is al-funun by Muhammad ibn Mahmud al-Amuli on arts and sciences during contemporary and ancient times. Before the citation Arnold pauses to note “that even in so extensive a survey he [the author al-Amuli] can find no place for mention of painting” (page 2). It is a remark he will make repeatedly because painting is all but ignored by Islamic historians simply because of the stigma attached to it. I am including Arnold’s full citation on calligraphy only to serve as an excellent example of the depth of Arnold’s research and also because I enjoyed reading the translation from the original Persian.

From here, Arnold proceeds cautiously to build his case. He does this by transporting the reader to the very founding of Islam in order to show Islam’s perplexing relationship with painters and painting as an art form. I thoroughly enjoying the historical angle of the first couple chapters. Here is another taste of how Arnold goes about his work, P.7:

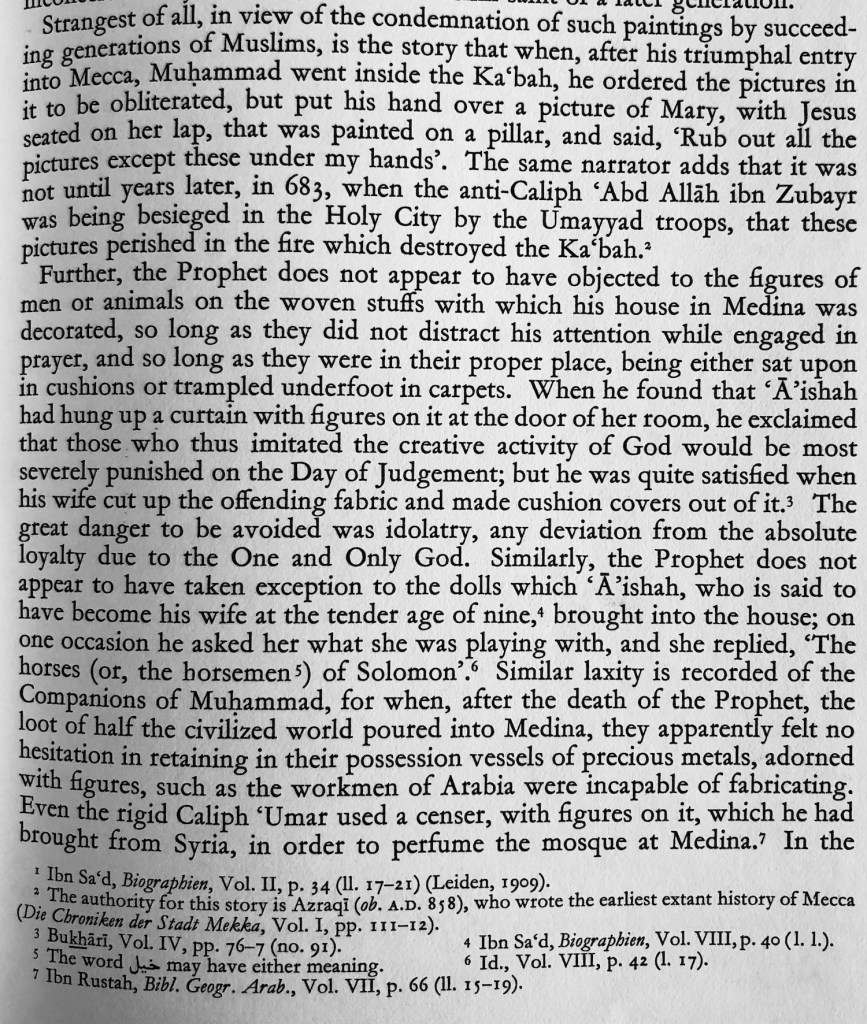

Arnold references the earliest of Prophet’s companions in an attempt to make his case that there was a noticeable increase in Islamic orthodoxy in subsequent generations of Muslims following the Prophet’s passing.

In the process of showing readers why pictorial art has such a horrible reputation in Islam, Arnold uses numerous sources—from Hadiths to original historical sources that he could get his hands on. At this point I should note that the author is a very proficient historian with an expert grasp on reading and understanding Arabic.

To show the relationship of between art and one of Prophet Muhammad’s earliest companions, Arnold writes, “Another companion of the Prophet, one of the earliest converts, Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, appears to have been untroubled by such scruples, for when after the capture of Ctesiphon in 637 he held a solemn prayer of thanksgiving in the great palace of the Sasanian kings, it was expressly stated that by the historian that he paid no heed to the figures of men and horses on the walls, but left them undisturbed. Indeed, these decorations appear to have survived the iconoclastic zeal of the Muslims for more than two centuries, judging from the description that Buhturi (ob. 897) gives of the pictures in the ruined palace.”

Most importantly, Arnold comes to the conclusion that “Primitive Muslim society, therefore, does not appear to have been so iconoclastic as later generations became, when the condemnation of pictorial and plastic art based on the Traditions ascribed to the Prophet had won general approval in Muslim society. The genesis of these Traditions is obscure, but by the second century of Muhammadan era compilations of them were being made and they were certainly by the time beginning to mould orthodox opinion, and in regard to plastic art in particular the laxity of the first generation of the faithful was giving way, except in the atmosphere of a pleasure-loving court, before the severe attitude that had found expression in the Traditions quoted above. It is significant of this hardening of opinion that a governor of Medina in A.D. 783 had the figures of the censer which [Caliph] ‘Umar had presented to the mosque of that city erased; he apparently could not tolerate what the most devoted Companion of the Prophet, the revered model for later generations, had regarded with indifference.”

This was a critically important example in showing how the faithful of the first generation of Muslims differed from later generations. It is very ironic that this is the path that was taken by the Muslim scholars of later generations since at its most basic level, the religion calls for Muslims to follow in the path of the Prophet and his companions. It’s almost as if the later generations were trying hard to out do each other in their individual level of piety.

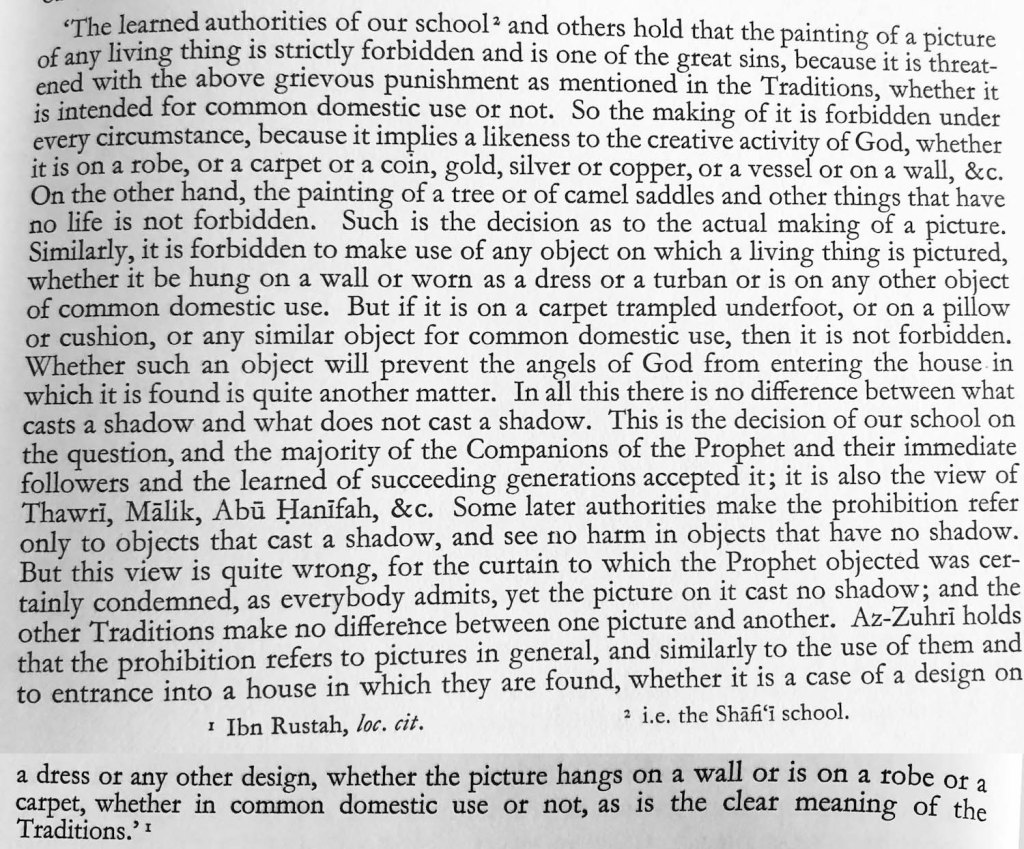

Arnold continues the previous quote to complete his theory about the progression of Islamic thought of later generations, writing, “When in the third century the Traditions took permanent and authoritative form in the great canonical collections connected with the names of Bukhari, Muslim and others, no further doubt was possible for the faithful as to the illegality of painting and sculpture, and the same condemnation was embodied in the accepted textbooks of Muslim law and was thus enforced by the highest legal opinion. A great legist of the thirteenth century, Nawawi, summed up the accepted docttrine in his own time in the following passage, and it may be taken as representing the orthodox view of succeeding generations also….” The author goes to cite a brief section of Nawawi’s writings that shows him putting great weight on the Hadiths. I will quote post the snippet below (p.9).

By the end of the book, I must admit, I was left a little confused, to put it lightly. It turns out that Islam has a very odd and somewhat perplexing relationship with pictorial art and the painters who create the art. It appears that painting suffered a painful death under the shadow of Islam’s hatred for all things within inhaling distance of idol-worshiping. Arnold goes to great lengths to plant seeds of doubt in what many believe to be “official” theories, but since critical historical evidence to backup his major claims have either been destroyed or lost over the course of hundreds of years and countless rulers of various degrees of Islamic orthodoxy, it ultimately makes it difficult to come to any concrete conclusions. Nevertheless, it is a worthwhile read for those curious enough to go on the journey.

I read this edition: Arnold, Sir Thomas W.. Painting in Islam: A Study of the Place of Pictorial Art in Muslim Culture. Dover Publications, Inc., 1965.

This 1st edition has the color paintings: Arnold, Sir Thomas W.. Painting in Islam: A Study of the Place of Pictorial Art in Muslim Culture. Oxford University Press, 1929.

Leave a comment