As a somewhat wounded America struggles with its democratic identity following the painful events at the U.S. Capitol building on January 6th, 2021, my goal is to help figure out a path forward.

Over the summer I read a wonderful biography of Muhammad Ali Jinnah by Hector Bolitho. Obviously, the tough thing about Jinnah is that he was a polarizing figure when it comes to modern South Asian history, so it isn’t exactly easy to find viewpoints that aren’t drowning in bias. Depending on where you live in post-colonial South Asia and regardless of your faith, your views and sentiments of Jinnah will range from being highly skeptical, bordering on hatred to hero-worshiping the man who in Pakistan is commonly known as Quaid-i-Azam (or “Great Leader”).

With that said, enter Mr. Bolitho. He appears to be a well-traveled man who doesn’t have an axe to grind on the topic, at least from what I read. Moreover, with a total of fifty-nine published books to Mr. Bolitho’s name by the time of his death in 1974, he was obviously a man up to the task and I have to say, the book has held up well! I’ve already said too much, but please do grab Jinnah, Creator of Pakistan by Hector Bolitho (1954) from your favorite used bookstore.

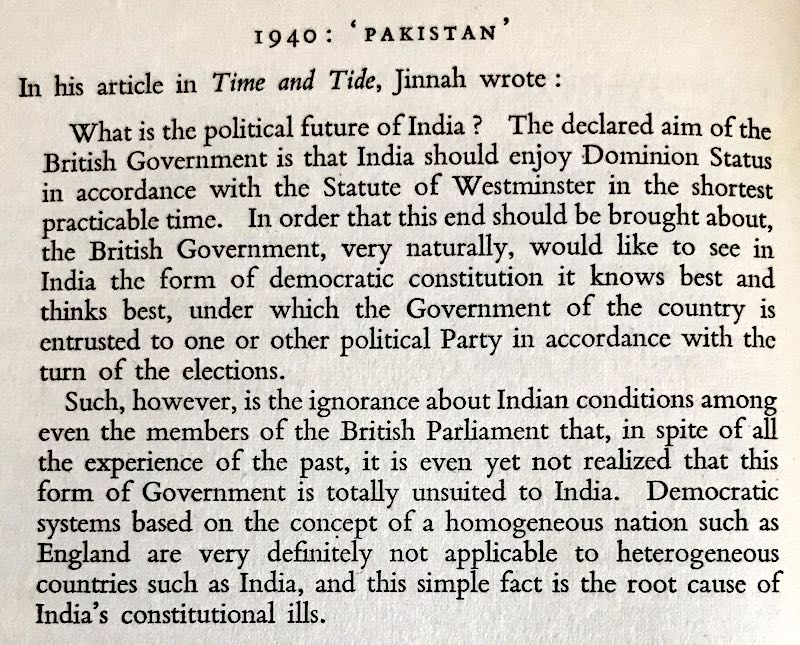

Now let’s turn our attention to my central point. In referencing this book, my intention is to to point out a very astute observation Jinnah makes about western democracy during the process of negotiating the formation of Pakistan. First to give some context, Bolitho attempts to get into Jinnah’s head by way of quoting from two published articles in English journals from 1940. Here are the direct quotes:

And finally, Jinnah writes, “Perhaps no truer description of India has been compressed into a paragraph” before concluding with the following:

“The British people, being Christians, sometimes forget the religious wars of their own history and today consider religion as a private and personal matter between man and god. This can never be the case in Hinduism and Islam, for both these religions are definite social codes which govern not so much man’s relation with his God, as man’s relation with his neighbor. They govern not only this law and culture but every aspect of his social life, and such religions, essentially exclusive, completely preclude that merging of identity and unity of thought on which Western democracy is based.” P. 126-7

So, what do these excerpts convey to us about western liberal democracy in 2021? Hopefully I am not oversimplifying this, but to me, it appears the stability of a given democracy relies heavily on the homogeneity of its citizens. In other words, diversity and democratic stability are inversely related.

If you think about Jinnah’s critical views in the context of the terrible events of January 6th, it begins to make a little sense when you consider the insurrectionists were largely a white crowd addressing what appears to be nostalgic grievances of an older (and far more homogeneous) America—an America that was once “great,” I guess. How America goes about reconciling these two Americas—the one from the past as the founders saw it and the one that it will inevitably become—will be interesting, especially when you consider the myriad of other variables including highly fragmented media landscape, income inequality, immigration, just to mention a few. Establishing a semblance of cohesiveness certainly won’t be easy, so let’s keep this wounded America in our prayers and hope for the best.

Leave a comment